I remember the first time I drove over the Mary McAleese bridge. It was less of a water crossing and more like passing through a gateway. This, it seemed to say, is a country that does great things. A towering crenellation summits the cable-stayed beauty, perched on two impossible looking legs straddling the bridge into the Boyne valley below.

It didn't have to be this way. There are any number of ways to build an ugly bridge, but its builders were allowed to make it pretty, and they were right to do that. With construction starting in 2000, the bridge marked the peak of the Celtic Tiger boom economy in Ireland, the boundary between two counties and the Northern edge of Dublin's formidable commuter belt. It looks part stringed instrument, part fortification and all gateway to the future.

Unfortunately though, much of our infrastructure isn't like this, and that's a great crime because it would be so easy for it to be much, much nicer.

Most of our infrastructure is like this overpass: Gloom-girdled, blockish and grey, speaking of austerity and a chronic loss of optimism.

I posted this image on social media and expected cynicism, but received hope and yearning instead: Sure, a few dyed in the wool cynics decried the cost of adding even the faintest screed of beauty to public works, but most pointed to examples elsewhere in the world where aesthetics were clearly part of the brief, and the cost of this was measured in imagination, not dollars.

Here's an example from Arizona, where different concrete moulds, a lick of paint and a dollop of creativity did what money didn't have to, and completely changed the look of the structure.

“But what's the point?” You might ask. “It's just a road!”

Exactly. Outside your own house, your commute is the thing you see the most. It's the portal between your two worlds and two personalities, and for many of us it's the only moment in the day we have to ourselves. A little bit of beauty eases the transition, clears the fog and opens our eyes.

And it goes a lot further than that.

If you have to list the most beautiful places in Earth, from Venice through the Great Pyramids to Mont-Saint-Michel, you'll see a list of civilizations at their zenith. It's in such times of optimism that we feel we can carve our place in the world for eternity, and that this carving should therefore be magnificent. Places like this come from moments where people want to mould the future into something fantastic. It's a stamp on a letter posted to the future, from us to them.

Look at the great things we made!

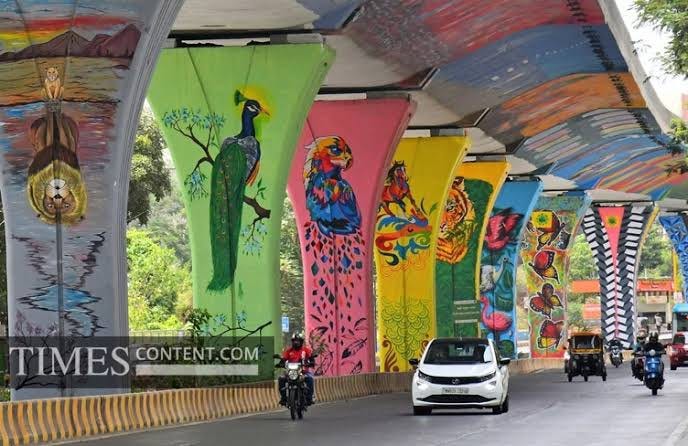

And it doesn't have to be the mark of greatness: It can be a mark of aspiration and hope as well. Look at these two images below, one from Mumbai and another from Tipperary Town, Ireland: Neither are the richest places in the world and neither have ‘made it’, but in both you find a little spark of something divine amidst the grime, where some paint and imagination created something wonderful on a canvas that we'd otherwise ignore.

The importance of this is profound. Remove the artistry and what's left? A forest of hectoring road signs and safety barriers, issuing familiar, unnecessary commandments:

Yield!

Give way!

Slow down!

Sometimes I play a game while driving, seeing how long I can go without seeing a sign or warning. If you had to hold your breath between each one you'd be in no danger; you could drive hours with no risk of passing out. They're an omnipresent intrusion of ugliness into our lives, unneeded handmaidens of the bureaucracy.

It has other consequences too: If all that is man-made is uglified, then we start to hold contempt for man-made creations in general, and seek to eliminate them from our life.

When HS2, the United Kingdom's new high speed rail project, was announced, it was to be a revolutionary project connecting the existing high speed rail connection with France to a dedicated route between London & Birmingham, and then up the spine of the country, in two branches connecting the prosperous South to the poorly-connected ex-industrial cities of the North.

Alas, so many fragile egos and NIMBYs in the crucial rural South were offended by the possibility of an ugly rail line staining their views of nature that almost half of that London-Birmingham route was built below ground level, at humongous expense. Fast-forward to the present and the cost of the project has become so embarrassingly bloated that the two Northern legs have been cancelled outright: The very part of the project that would have been most transformative to peoples’ lives.

Now, I'm not saying that a few murals and pleasingly fluted concrete would have helped here, but it can't be a coincidence that in a country with so much enforced infrastructural ugliness, the response of the public to more of it is hostility. Aesthetics matter, and so by chasing pennies in the blockish uglification of our infrastructure over many decades, we ended up wiping out tens of billions right where it would have done the most good.

I've been guilty of it myself, too. When introducing production lines I have in the past pushed for blockish utilitarianism to save pennies when a slick facade or an appealing robot would have looked more appealing… and even in production machinery that matters, because when the Very Important People come to see what you've built with their money they want to be impressed by it, or you won't get any more.

Perhaps the only way out of this, in the West, is to scour the lingering stain of Treasury Brain, where cost efficiency is the god we must all pay homage to, and introduce a little more Vision into our world.

We won't bean-count our way to a better future.

And we won't want to go there at all if it doesn't look nice.

Let's pay less heed to the accountants, and pay the artists.