Touching Heaven

How to (actually) reach the stars.

Science fiction is a fine genre to get lost in.

Now, normally that sentence would instantly lose most of my readership; better to run the mainstream gauntlet and talk about politics and dietary deficiencies, perhaps? But somehow I've got a feeling that the kind of person willing to read about how, say, Titanium is made won't be put off by a bit of sci-fi.

Except…

Amidst the weird aliens and ancient artifacts of fiction, up there in the firmament where people cruise around like old-school naval battalions in hard vacuum lies a single, massive suspension of disbelief. It's one that underpins almost all science fiction, because if you take even a tiny chip off it, the scouring light of cold reality will ruin your story! Reading about aliens, AIs and distant star systems only works if you answer one big question:

How the hell do we get there?

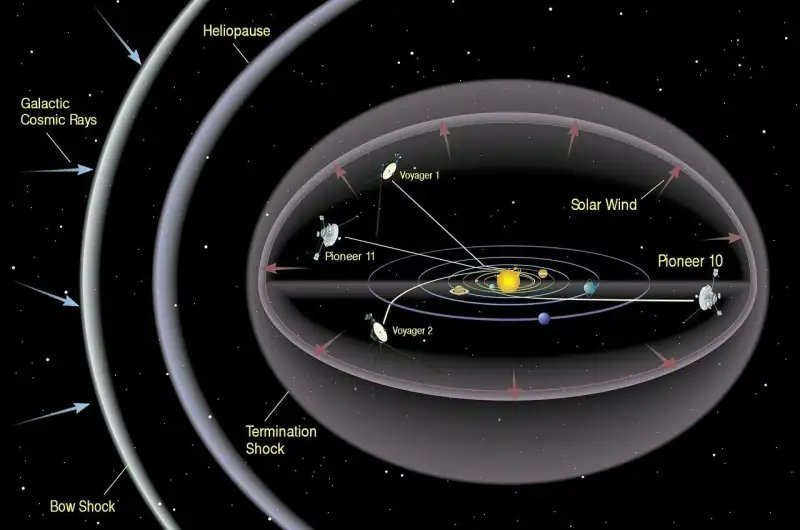

The furthest man-made object from Earth is the Voyager 1 deep-space probe. After taking gravitational slingshots off Jupiter and Saturn it's tearing into interstellar space at an impressive seventeen kilometres per second, which means that it would do my morning commute to Limerick in two and a half seconds, rather than most of an hour. Not bad. It was also launched in 1977, so it’s had almost half a century to put down some serious distance. How far has it gotten?

Voyager 1 is covering 523 million kilometres a year, or three and a half times the distance of the Earth from the sun. If it just happened to be aimed directly at Alpha Centauri, our nearest star, it would take not fifty years, not a hundred but 80,000 years to cross the gulf.

Well, damn.

To put it another way, let's imagine that our sun was only 1 metre wide (rather than a million kilometres). At this scale Earth, our entire planet, would be the size of a small grape about one football field's distance away from the fiery miniature sun.

And at this scale, where the distance from Earth to the sun is the length of a football field, the distance to our nearest star is about the same as getting on a plane and flying non-stop around the entire planet.

Space, as they say, is really big.

It's so ridiculously, mind-wreckingly enormous that the act of getting to the next star would be, by some distance, the hardest thing we're ever likely to do as a species. It's so difficult that you could shoot down almost every book in the science-fiction genre just by saying “nope. Not gonna happen.”

But it isn't actually impossible.

Want to know how to cross the infinite sea? We're about to find out…

1: The Need for Speed.

However you parse it, crossing the wine dark seas of interstellar infinity means you need to go absurdly fast, unless you’re happy with some distant chimp-like descendent of yours scratching its noggin in puzzlement at the light of a new sun, its space-borne habitat finally heaving into view of Alpha Centauri.

-Oh, before we continue: I’m going to be keeping a log of clichés as we go, because this subject attracts them like flies to shit (+1 cliché), and ‘wine-dark seas’ definitely counts as another, so that’s 2 in the cliché bucket so far. There’ll be more, of a science-fiction-y nature as we go.

Whatever. Let’s give ourselves a target: Alpha Centauri, and a duration… maybe a hundred years max? Alpha Centauri, our nearest star, is a teasing 4.37 light years away, meaning that signals sent from here to there would take 4.37 years to get there. If a return signal was sent, then the full round-trip of data, a sort of interstellar “How’re you doing? Nice weather we’re having!” would take slightly less time than the full run of the NBC series Friends. That’s one for fans of mediocre comedy. If we send something that takes a hundred years to get there, then the receipt of a triumphal “Eagle Has Landed” would take 104.37 years after launch. Not ideal, since anyone on the project would long since be dead, but perhaps their children could carry on the grand Masonic tradition of interstellar exploration and give a thanks to their dear old dad, or grand-dad.

That’s a +3 in the cliché bucket for the Eagle Has Landed, by the way. This might become a little frequent, so I’ll start bucketing them up…

Let’s say that one hundred years is our maximum duration to get to Alpha Centauri and either pass a ship through if it’s a probe or stop it in a suitable orbit if it’s a colony. Maybe halving it to fifty years would give a shot at some of the project team still being alive to salute the heavens when the triumphant signal finally arrives. How fast do we need to go for that?

If we assume that the majority of that time will be spent coasting, then you need to get the ship to a little over 4.4% of the speed of light, or 13,200 kilometres per second to get there in a century. Now the fastest man-made object ever is the Parker Solar Probe, which made a close pass into the sun’s corona at a blistering 192 kilometres per second. This is bonkers fast, but nowhere near enough for the stars, so clearly we need something a little different. Let’s check out our options.

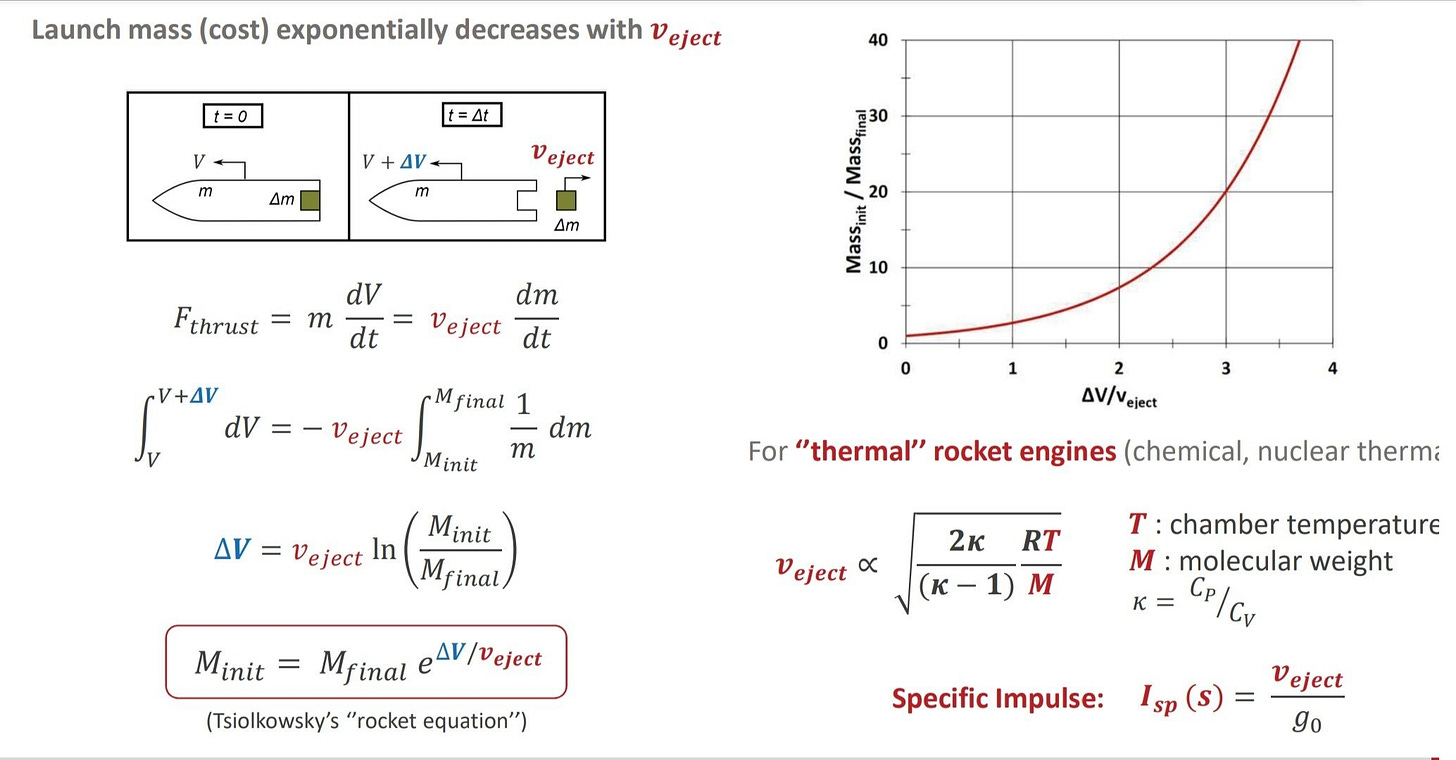

The first thing to rule out is normal chemical rockets, which don’t have anywhere near enough pop for interstellar missions. This is governed by the mathematical tyrant that is the Tsiolkowsky rocket equation, which states that the mass of propellant for a rocket rises exponentially with the change of velocity you need the rocket to make. This varies with the exhaust speed of your rocket, which in the case of the best chemical rockets (hydrogen-oxygen burners) is about 4.5 kilometres per second. This sounds fast until you work out that if you use such a rocket to accelerate to speeds that will let you cross the stars within a single lifetime, you’ll need more propellant than exists in the entire universe.

Well, damn.

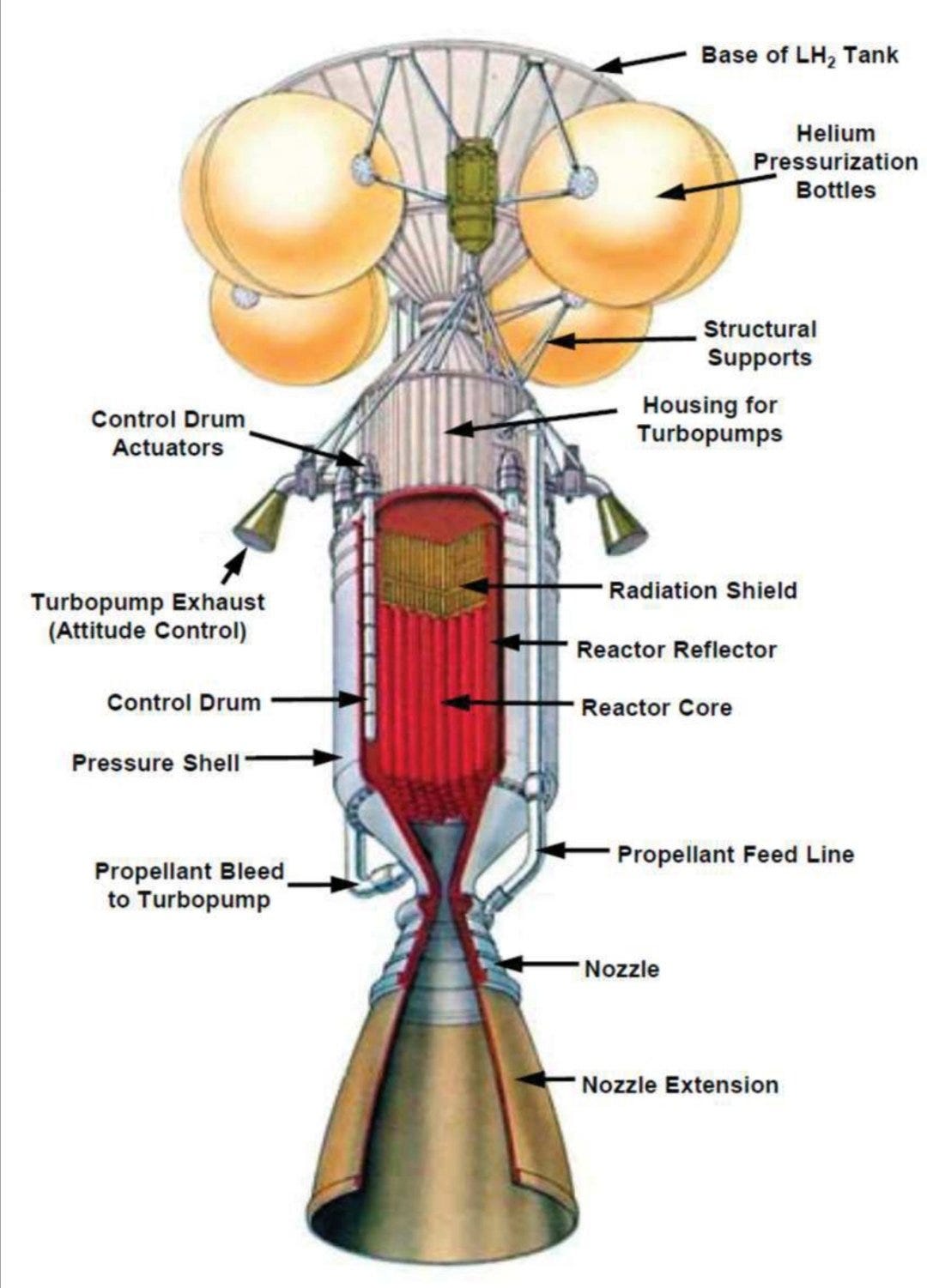

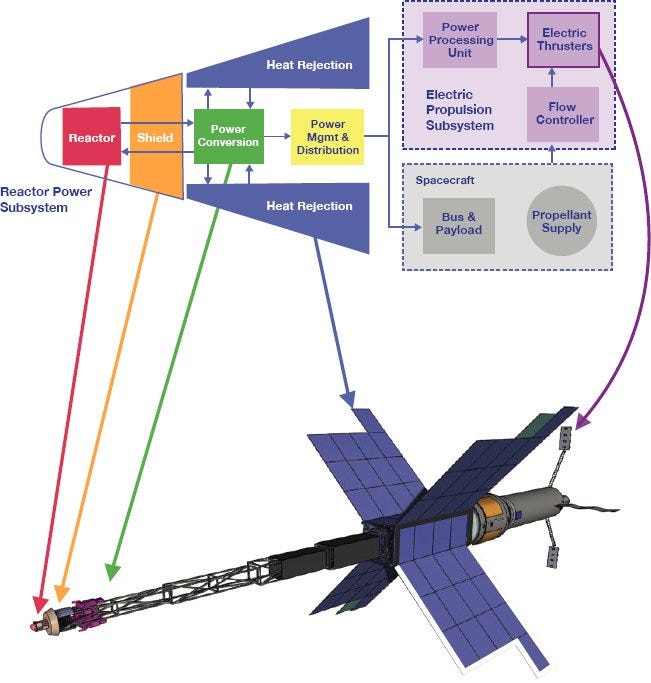

What we need is to up that exhaust velocity, so the logical next step is to ask: Why not use a nuclear thermal rocket instead? I’ve written on this in the past, as due to the low molar weight of hydrogen (versus the water exhaust of a hydrolox chemical engine) you can get much much higher exhaust velocity of 8km/s versus the 4.5 of the hydrogen-burner. This gives a specific impulse (think ‘rocket fuel efficiency’) of 800 seconds. Not bad, and it might be handy if you want to ride a gas-cooled nuclear reactor to Jupiter, but for another star it’s hopeless. Next…

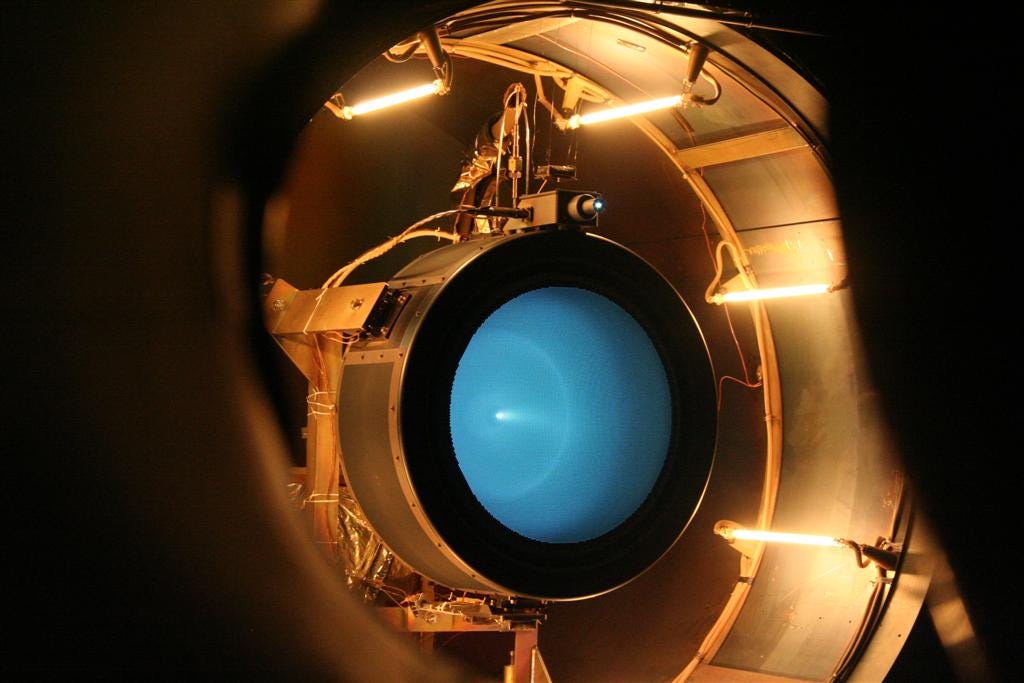

Ion engines could do better, relying on the acceleration of ions such as Xenon in a strong electric field (though other gases are available). These produce exhaust velocities and specific impulse figures about ten times higher than chemical rockets: You’re now knocking out exhaust at a velocity of 20-50 kilometres per second, although the drawback is that the actual thrust they’re capable of putting out is correspondingly feeble.

A few kilowatts of electrical power will give you thrust in the region of 25-250 milli-Newtons. In normal human-speak, that’s somewhere between the weight on Earth of a piece of paper and a packet of crisps (chips to you Americans). This makes ion engines efficient but extraordinarily dull, like a Toyota Prius if you could teach it orbital mechanics. In principle though you could still apply them to a human colony ship, if you were prepared to wait a long time for acceleration, but that's still a multi-millennium travel time: It would be as if the ancient Egyptians sent a mission to space… that’s sci-fi cliché number 4, by the way.

You’d also need to power the thing: Solar power is fine & dandy, but that gets less useful the further away you get from the sun, and going interstellar means by definition that you’re a long, long, long way off, not so much plying the oceans of space as swimming through an endless abyss.

How cheerful.

Well, that ends the list of present-day propulsion systems and not one of them makes the cut, so now’s the time to pour yourself a stiff drink, give your head a bit of a wobble and join me on a journey through the wilder concepts out there. It starts mad and, believe me, gets madder and madder as we go.

2: Snap, Crackle and Pop!

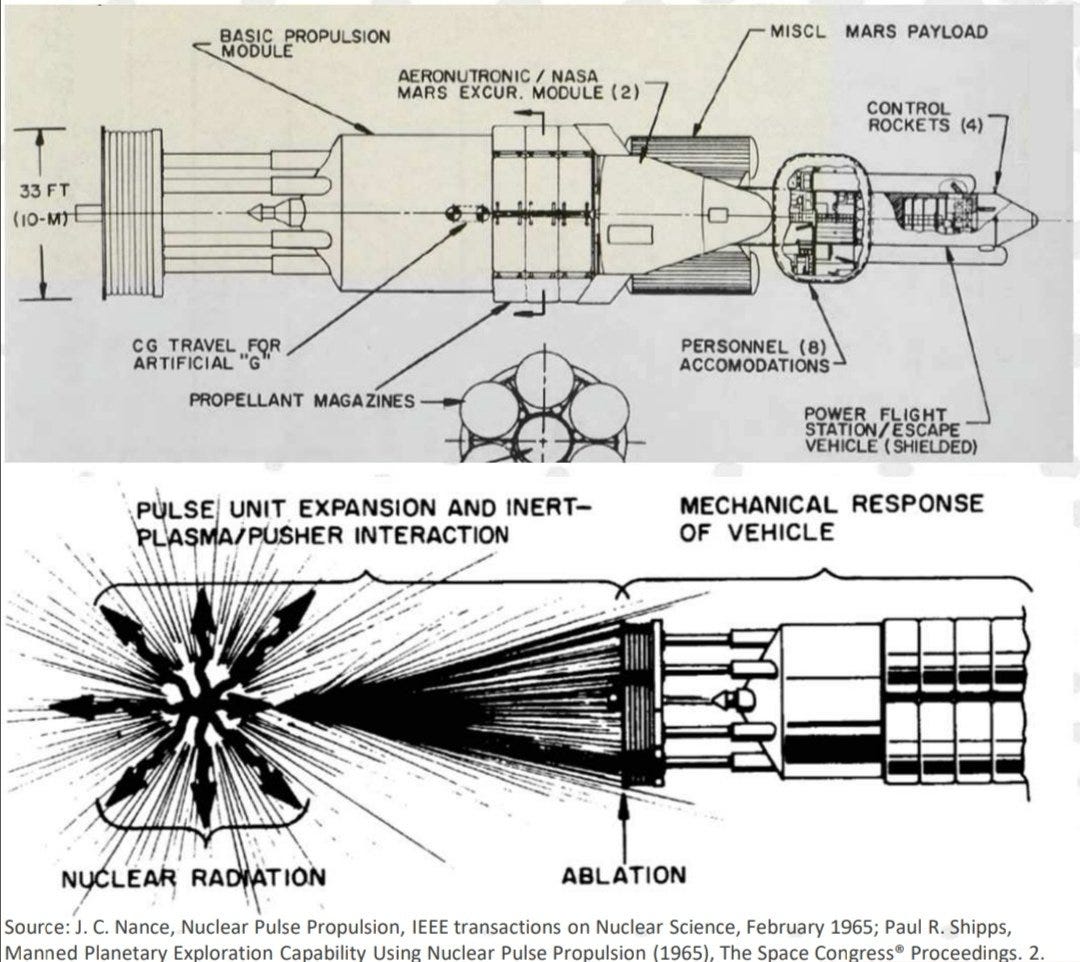

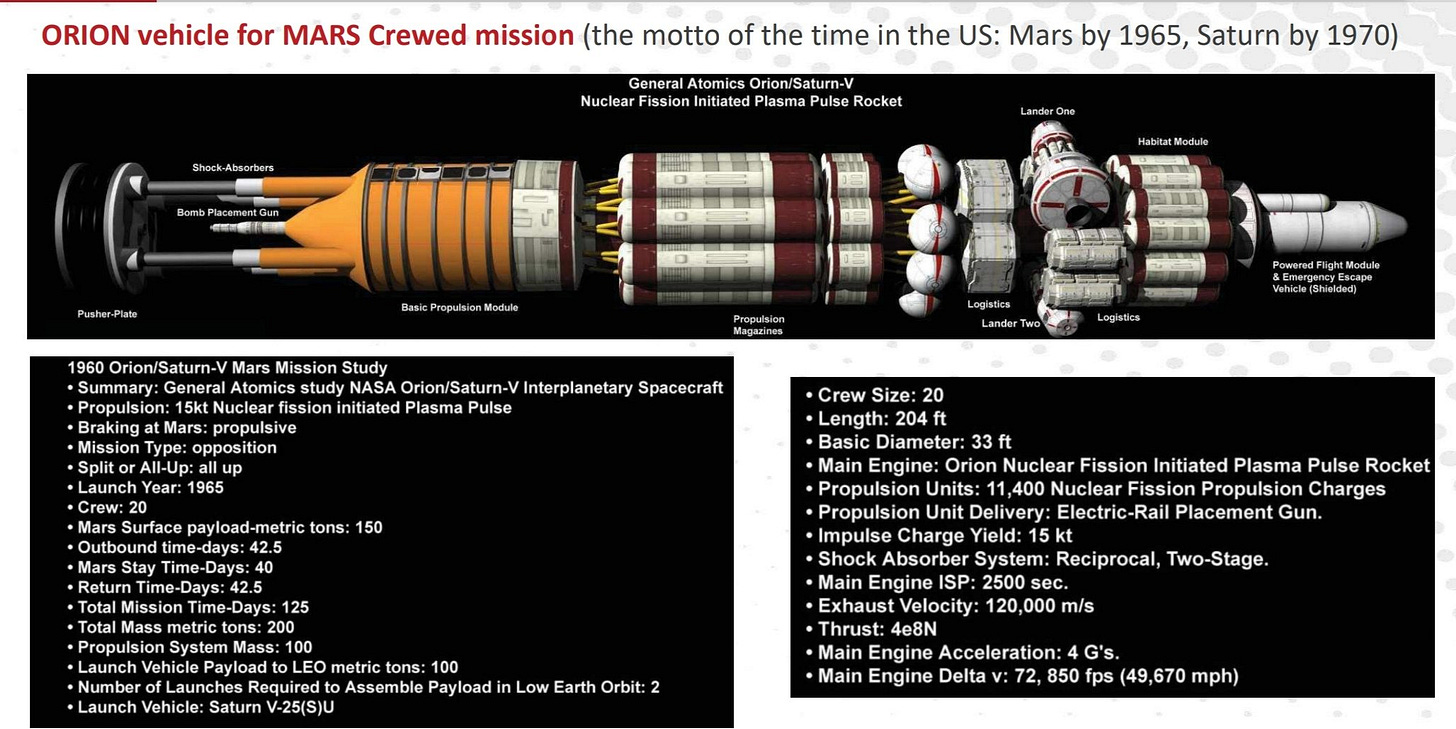

As is ever the case in matters atomic, Project Orion was initiated in the go-go 1950s and 60s in the United States; the atomic age. This was an era pre-Chernobyl, pre-Windscale and pre-Three-Mile-Island, when our nuclear ambition had probably slightly outpaced our safety culture, but also wasn’t paralysed by it. The output was unique aberrations like the Orion project. This was a study into an interplanetary heavy-lift spacecraft powered by nuclear pulse propulsion. “What is that?” I hear you cry.

Well the ‘pulse’ is obvious enough, which is a propulsion system that delivers in a discontinuous series of pulses rather than as a continuous exhaust stream. The ‘nuclear’ descriptor should, by now, become obvious.

Simply put, Project Orion was a spaceship that periodically lobbed a nuclear bomb out of the rear and rode the blast. Then sent another, and another…

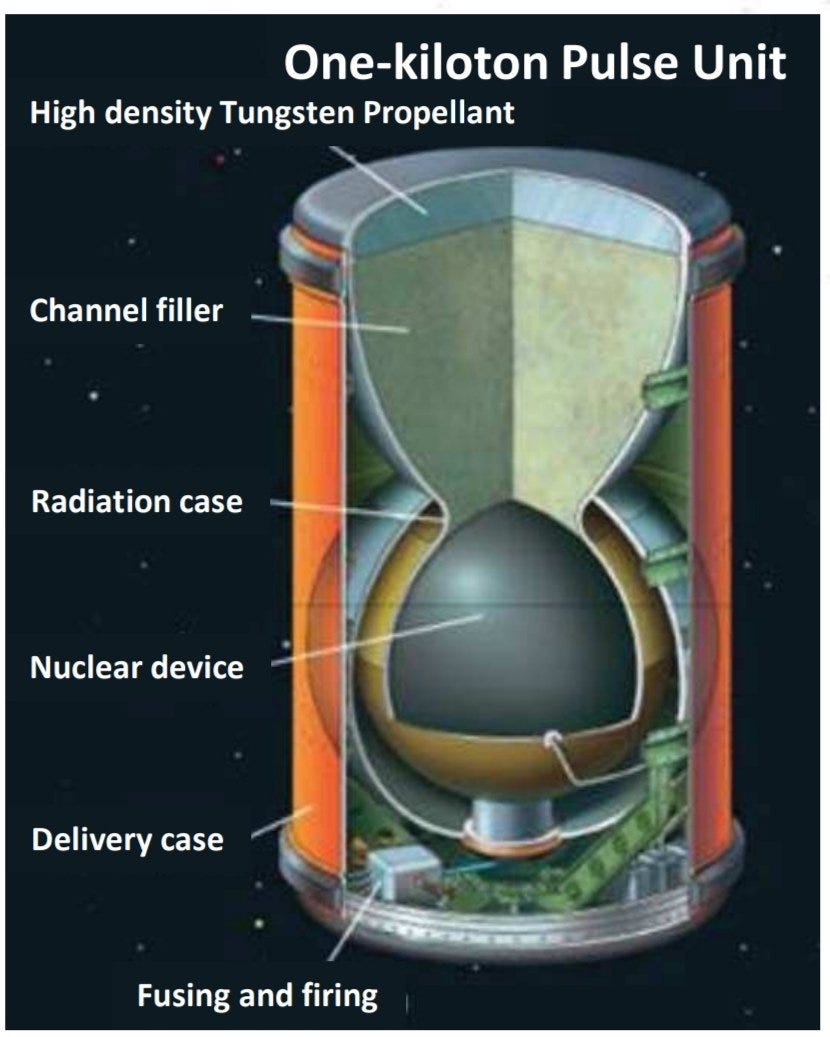

The nuclear devices would be small, small for nukes anyway, and would be the atomic equivalent of a ‘shaped charge’, with an internal channel and a high density tungsten cap as a propellant. These would detonate some distance behind the Orion spaceship, where an ablative pusher plate would take the onslaught of hard radiation, hyper-velocity explosion remnants and the propellant plasma that the tungsten plate would instantly become. This ablative shield, hit by the full fury of atomic fire, would compress a two-stage shock absorber: One to take the high-frequency shock impulse of the detonation and spread it around a little and another, larger, second-stage shock absorber that would ‘smooth’ the pulsed inputs of large numbers of nukes going off one after the other, creating a thrust force that would propel the spaceship on its way.

Is this complex? Of course it is! You need a foolproof way to trickle feed nuke after nuke through a gun that cannot admit a returning plasma blast wave, each device must detonate precisely (outside the spaceship) every time and avoid out-of-sync or early detonations that could wreck the ship. The ablative plate and shock absorbers are without real precedent in the engineering world and would need designing for the task, radiation shielding would need to be provided by a colossal bulk of material, most of it co-located in the pusher plate. There is also the question of erosion, or the unknown aspects of it: Theoretically a steel plate would ablate in the region of 1mm per blast, or less if a coolant of barrier layer is injected, but this leaves aside specific erosion concentration problems. Firstly, high speed debris can create point damage. Secondly, the turbulent characteristics of the nuclear plasma are unknown. Thirdly, neutron exposure does funny things to metals, as the fusion reactor industry (and the conventional nuclear one) knows well. And there’s testing as well, though modern computational simulation and specialist test facilities lower the risk premium on this: There’s probably no need to fire off a thousand nukes behind a test craft just to be sure.

Sadly, the geopolitical and public health ramifications of a nuke-spitting spaceship are probably sufficient to put an end to Orion, which is a shame in a way, and a relief in another way. A spacecraft that casually flings out a superpower’s-worth of nuclear snap, crackle & pop is a bit of an ask.

On the other hand, Orion combines the necessity of a high exhaust velocity (up to 31 kilometres per second) with the utility of proper amounts of thrust, measured in the mega-Newtons and not milli-Newtons. This, combined with the sheer robustness required of the concept, means that the Orion spaceship can be BIG! There’s no need for the spindly solar arrays and lightweight tension-webbed designs that we’re all used to in space. Instead, an Orion spacecraft would be like a World War II battleship in the sky. Make way for the Space Battleship Yamato, perhaps?

Sadly but unbelievably, however, Orion just doesn’t have enough oomph for an interstellar trip. Remember that the exhaust velocity is only in the region of 31km/s max, which is impressive but out-stripped by the feeble yet practical ion engine. In addition to this, a lot of the explosive potential of the charge is wasted, so it’s not the most efficient design… but really who cares about efficiency when you’re pogo-stick flying on nuclear Armageddon? Come on, now.

Be that as it may, hilariously the concept may have been accidentally tested. In 1957 a nuclear containment test called ‘Pascal B’ was conducted as part of ‘Operation Plumbbob’, a hilariously titled series of nuclear tests, of which the 1950s were replete. Pascal B was an underground test, and because of the unanticipated spiciness of ‘Pascal A’ the previous year, the borehole down which the nuclear bomb had been positioned, hundreds of metres down, was fixed with a steel containment cap. This huge one-ton block of iron ‘should’ have sealed the borehole, although the scientist in charge, Robert Brownlee, was convinced otherwise.

Robert was right.

Pascal B was a ‘small’ nuke, but when it detonated the blast went straight up the test shaft and into the containment plate, which was never found. A high speed camera focused on the event, capable of taking a thousand pictures a second, saw the plate in a single frame, ascending skywards like a nuclear bat out of hell. Brownlee calculated later that, taking the time between each frame, you could estimate that the plate was moving at six times the escape velocity of planet Earth. Most likely it was vapourised by compression heating as it soared through the atmosphere, but like many I have a soft spot for the Pascal B plate, and hope that somehow it survived.

And one day, far beyond the reach of our solar system, up among the Oort cloud and an infinity of comets churning through the black, something goes “Beep!” on the long range scanner of a little green man… who is instantly flattened by an atomic manhole.

We can hope.

Cliché count: At least eight so far, between nuke-spitting, space-battleship Yamato, “nuclear bat out of hell” and “atomic age”. Let’s rev this up!

3: Salt Water Taffy.

Believe it or not, Project Orion isn't the most batshit-crazy interstellar concept on this list, for there's another fission-powered fiend that's even more psychotic.

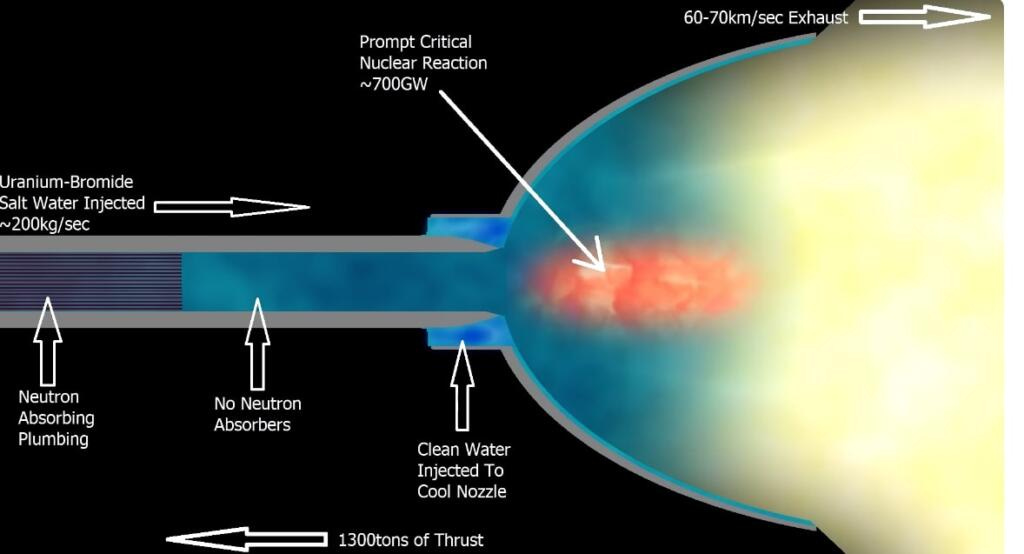

The nuclear salt-water rocket.

Proposed by aerospace engineering and terraforming enthusiast Robert Zubrin, the nuclear salt-water rocket, though technologically at an earlier stage of development than Orion, actually does have the theoretical ability to function as a workable interstellar propulsion system, and unlike the (saner and more sustainable) alternatives later in this article doesn't require the resources of an industrialised solar system to pull it off.

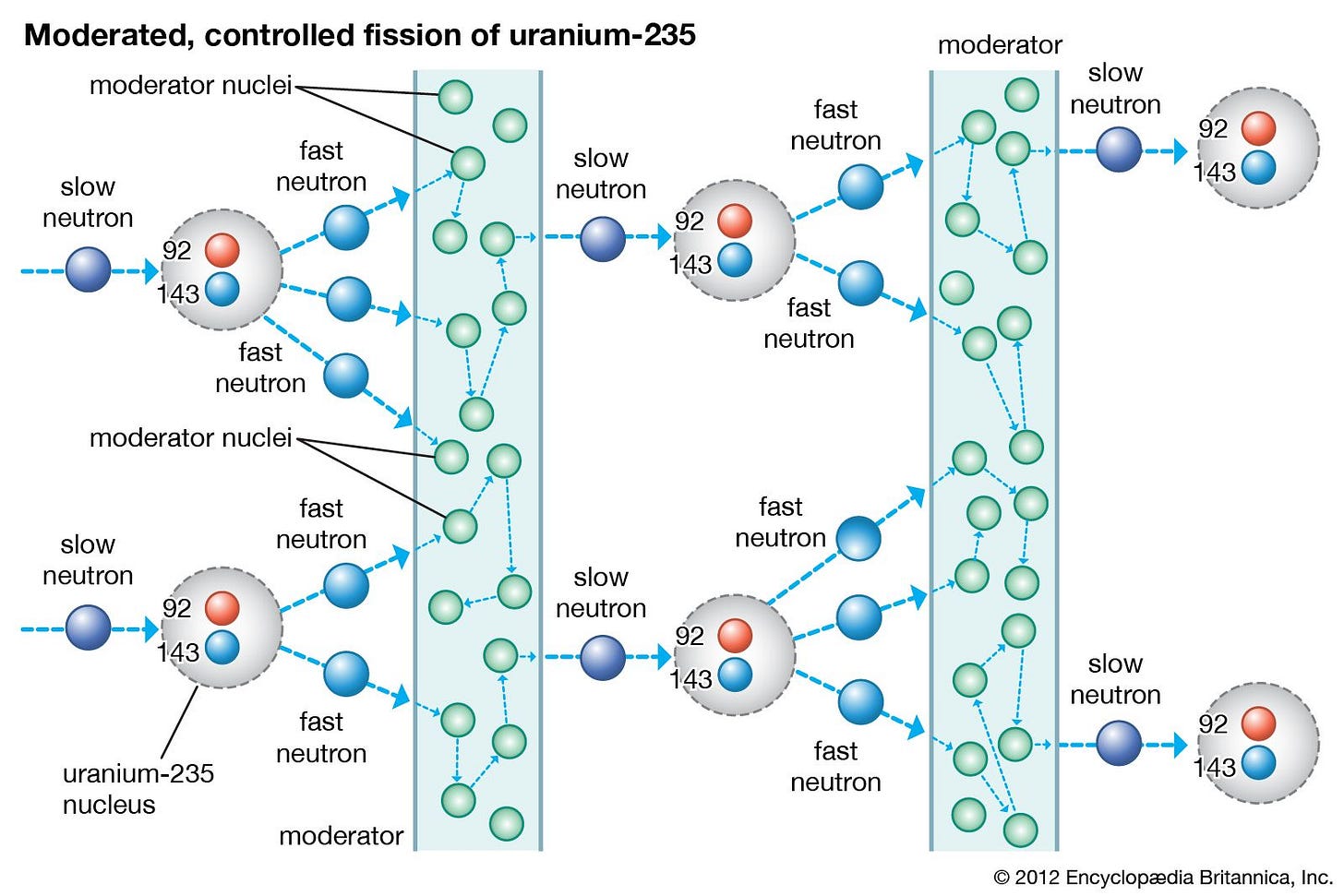

Simply put, in this pragmatic and terrifying creation, salts of either Plutonium or highly enriched Uranium salts (such as uranium tetrabromide) are dissolved in water and contained in a network of well-spaced boron carbide pipes. The water functions as a neutron moderator (promoting a fission reaction) and the boron carbide is a neutron absorber, which suppresses fission chain reactions, along with the physical separation of the salts while the fuel is in storage. The salt solution is then pumped at considerable pressure and velocity to a reaction chamber and a divergent nozzle and, brought to one spot and free of the cloying embrace of boron carbide, a prompt fission chain reaction occurs. This consumes much of the fissile U235 or plutonium, dissociates the water and creates a fast expanding plasma that reaches hundreds of kilometres per second exhaust velocity, depending on design. Even the ‘basic’ Zubrin design with 20% enriched Uranium gets you many megaNewtons of thrust and an exhaust velocity of 66km/s, which basically makes the solar system your plaything, as long as you don't mind holding your rodeo hat on and riding the last instant of the Chernobyl reactor all the way to your destination.

And some variants of the design could get thousands of kilometres per second of exhaust velocity and an interstellar mission.

Wait, what now?

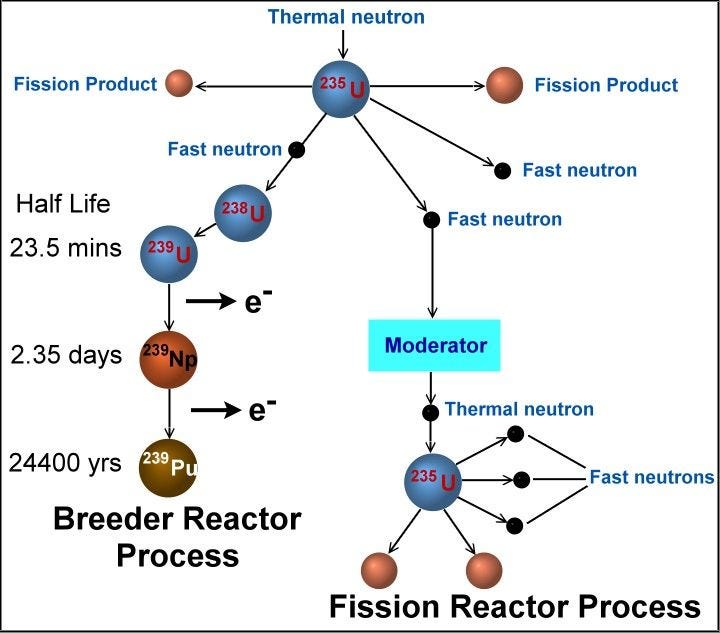

Well, Zubrin’s design assumed 20% enriched Uranium and a relatively low yield in the water solution, but if you’re really going to push the boat out you don’t need to restrict yourself to that. Remember that the ‘enrichment number’ is the percentage of the fissile fuel component that is made up of fissile Uranium 235, 233 or Plutonium 239, as opposed to the far more common U238. In nature the average ‘enrichment’ of Uranium deposits is 0.7%, while in most commercial nuclear reactors it’s about 3%-5%. Zubrin’s salt water rocket concept assumed a hefty 20% enrichment level, which is about the point at which you’d start to describe the fuel as being “highly enriched”.

But fuck it, we can do better than that! We want a high speed exhaust, so why not kick the enrichment level all the way up to 90%? That means you’re dealing with ‘weapons grade’ Uranium, which is exactly what that sounds like: Bomb stuff. Handle with extreme caution.

The nuclear salt water rocket is not ‘extreme caution’. Not by any means.

But if you could somehow get your engineering right and be able to play with real bomb-stuff, you’re in business for the interstellar travel game. If you have a pretty salty solution of 2% Uranium tetrabromide (and 98% water), and that Uranium salt is 90% enriched, then as well as creating the most terrifying possible means of travel you’ve potentially given yourself a means to slip the surly bonds of our sun and knock on the door of Alpha Centauri. If you could engineer a usable nozzle with an efficiency of 0.9 (not an easy task for a controlled nuclear explosion, granted), and use 2,700 tons of propellant, then you could propel a 300 ton spaceship to 3.63% the speed of light with an exhaust velocity of 4,725 kilometres per second! This would cover the distance from Earth to Alpha Centauri in…

120 years. OK, so it’s still a bit slow, and nine-tenths of our starship is propellant, but it’s close to achieving our goal at least!

Now, there remain problems with the nuclear salt-water rocket, and obviously one of them is that it’s just flat-out bare-bottomed bonkers. For another, nobody knows how to create a rocket nozzle that can withstand atomic fury for any sustained period. In principle most of the actual fission happens outside the rocket itself if you do things right and eject the propellant fast enough, but the further back it happens, the lower your efficiency goes. You could also, of course, use film cooling on your nozzle surfaces, much as we do with chemical rockets today using liquid oxygen (perhaps with water in this case), but this strains credulity if you’re trying to cool a surface against something just one step away from a nuclear detonation. Hmm.

You could potentially use a magnetic nozzle and stop the fission products contacting the walls at all, but that assumes that every ounce of propellant has become ionised plasma, which it might not have. More on that later.

And of course you want to stop the reaction from progressing upstream. That could cause excess fission in your stored fuel, rapidly disintegrate your neutron absorbing fuel tubes and convert your spaceship into a giant fiery nuclear fart. In principle you can do this just by injecting your propellant really really fast, to outpace the speed at which the colossal torrent of neutrons released by your fission flare can propagate upstream towards your stored fuel.

Let's quantify that. A thermal neutron can move in water at about 2.2 km/s, so your fuel injection speed needs to be at around this level… but fast neutrons released from fission can travel over a thousand times faster, and it takes four or five microseconds for fast neutrons to slow to thermal speeds in water, or about 20-25 metres back up your nozzle. Depending on the size of your rocket and where most of the fission is occurring, that could work.

Oh, and you still need to inject your propellant at one or two kilometres per second, which might be above the speed of sound in water. It certainly gives you a challenge with your pumps. Maybe you could power them with returning nozzle cooling water, or separately with chemical rockets firing into turbines? Who knows. It’d be a complicated start-up sequence anyway, with a high price for failure.

Basically, it’s all a bit scary.

But let’s push the boat out: If a 90% fuel fraction can get us to Alpha Centauri in 120 years, can we go one better?

If that 300 ton starship was instead encased in a 30,000 ton ice asteroid and you used 7,500 tons of fissile fuel then at the price of a 99% fuel fraction (meaning that only 1% of this accumulated bulk is actually starship) you could hit speeds high enough to cross the infinite gulf in ‘only’ sixty years. You’d have to do fuel processing on-board to use all that ice, but that’s a small price to pay. Hell, you could drink it too, or use it for ice-cubes to cool your whisky if you’re a barbarian. There are no flies in this ice!

But real people drink their whisky neat. You know this.

Coasting to the stars in a nuclear iceberg. Sure. Why not? You'd need a stiff drink for that.

If you fuelled this beastie with Uranium 235 then all this, and Alpha Centauri, could be yours… at the cost of our entire global stockpile of highly enriched Uranium. It’s better than using it for bombs, I guess.

You could always use fast breeder reactors to produce Plutonium or U233 from natural Uranium or Thorium though, and then you’ve got enough for thousands of flights to Alpha Centauri if you want, but maybe don’t run your washing machine at peak hours, because we’d need some other way of keeping the lights on in that case.

So: The salt-water rocket. The psychopath’s mode of interstellar travel. Spot any aliens coming in one of these and you’d best steer well clear, because they’re not right in the head. Is there a better way?

Yes, there are two! But to access them, we first need to step outside our fragile blue orb, stretch our legs and industrialize the solar system…

(Cliché count: 11. Cowboy nuke-riding, surly bonds, colony iceberg…)

4: Fusion Food!

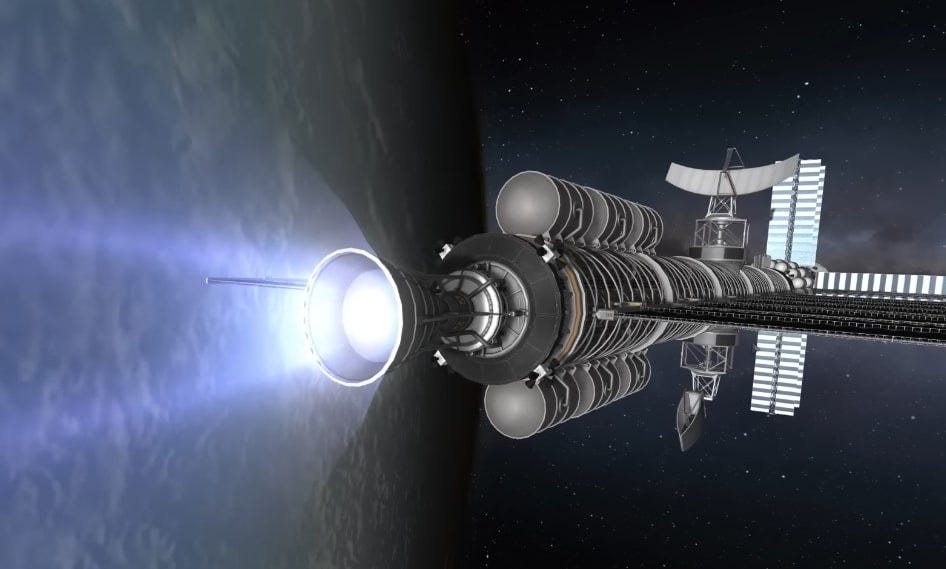

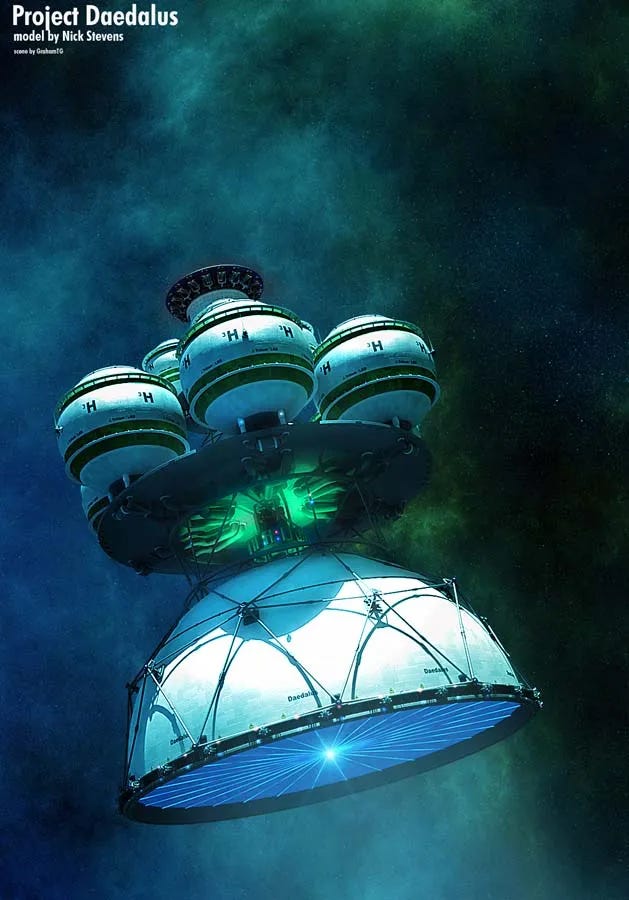

Its name was Project Daedalus.

A tiny pellet arcs through the deep void, faintly glistening in the timeless light of stars. The casual light of centuries past twinkles on its smooth, deep-frozen surface. Silently it passes in front of a vast shadow, finding itself at the apex of a colossal bell-shape that cuts the universe in two.

All at once the sky flares as dozens of beams hit it from every angle. Defeated, the pellet collapses, implodes, grows beyond heat and then explodes. A tiny new sun screams at the universe for just an instant, and behind it another pellet approaches, and another, and another.