The long march of supply chains, in which are carried your iPhone and your Argentinian beef, are powered by merchant shipping. The great beasts, rust-stained and stubborn, ply the world's oceans for decades, unseen from slick city showrooms but tended to by diesel powered armies in every port. Container after container in their monitored millions make up the blood cells of our global economy, ferried by unseen leviathans.

The container ship. The oil tanker. The LNG transport. The broken mules of prosperity, our entire civilization rests on their broad shoulders, and someday they will float no more. Systems failing, superstructure rotting, engines and generators worn-out, they must place themselves at the ship-breakers’ mercy.

There is a beach, endless and flat, its sand bound by oil and air tainted by strange fumes, where this happens.

It's where the ships come to die.

1: The Shanty of the ship-breakers.

As recently as 2023, the world’s combined merchant shipping fleet had reached a total of 2.3 billion deadweight tons, or about ten million statues of liberty. The vast majority of this muscular army of floating steel, 85% of it, is in the form of colossal bulk carriers, fuel tankers and container ships, and the logic of this is simple: The ocean resists movement like any substance, and it resists it in rough proportion to the wetted area of the hull. The hull of a ship is wrapped around a huge bulk volume, which displaces the water, and when the mass of the displaced water equals the mass of the ship, it floats. -And because the wetted area of the hull, and therefore drag, increases with the second power, while the displacement volume increases with the third power, it follows that for long distances the most efficient way to move anything anywhere is in a gargantuan ship.

And so it is.

This simple truism is the reason that our oceans are choked with cyclopean beasts, and why the combined mass of every human on the planet is outweighed four times over by the mass of our merchant shipping. It’s also why for all of us, every thirty years or so, a mass of floating steel weighing about four times you needs recycling.

Most of our merchant shipping is built in gigantic heavily-mechanised yards in China and South Korea, the new homes of ship-building. In such places are the safeguards, quality controls and heavy mechanisation that you would expect of any large bespoke engineering operation, but scrapping is not like this.

The busiest breakers’ yards in the world are in India and Bangladesh, and so our giant is likely to make its last voyage there, to either the Arabian Sea or the Bay of Bengal, to Alang on the West coast of India, or Chittagong in Bangladesh. There are other breaking yards, but these are the biggest and likely to offer the best price for a floating hulk.

Both of these places are characterised by long, flat beaches with significant tides, which helps with the first stage of the breaking operation: Getting the ship onto the beach! The vessel is first emptied of cargo and ballast, drained of almost all fuel & handed over to the breaking yard, who will provide it with a special pilot: A captain-for-a-day who has one very important duty…

…To ram the monster up the beach at high tide, until it can go no further.

Though the paperwork will have been signed some time ago by this stage, and the ownership transferred, this is the moment where the ship physically begins its demise, for once beached it can no longer move. Goliath is stilled, tied-down and surrounded by Lilliputians, who wish it destroyed.

The tide and the pilot have done what they can, but to stop the ocean reclaiming its own the ship must now be dragged. Chains & cables are fixed to the vessel, carried -in an appropriate echo- by human chains of labourers. Once this is done the vessel can slowly be dragged further up the beach before it settles. A breaking yard is a brutal workplace, and this early stage of destruction, which is merely prep-work, is in fact among the most hazardous acts in the yard, for the forces involved are beyond human, and a decoupled or snapping cable is an immediate and terminal danger for anyone close by. A lashing cable, carrying hundreds of tons of pent-up load, will cut a man in two given the chance.

With this base act completed, the ship must be further prepared for the act of breaking: A giant ship’s oil tanks are a serious hazard, and while mostly empty there will still be plenty on-board to become fire or explosion risks; a build-up of fumes, in a mostly empty tank, can become an explosive mixture that will ignite with only slight provocation. To mitigate this, the tanks must be completely drained: One grim but commonly-practised method to resolve this is simply to flame-cut a path into the bunker fuel tanks at low tide and wait, allowing nature to rinse the tank clean with the rise & fall of successive tides. Obviously this comes with attendant environmental risk, but it’s cheap and tempting.

So what now? Our hulk is beached, embarrassed and helpless. Its tanks are ruptured, its lifeblood drained and what is left of its rusty soul looks to the shore, where a shanty town rims a yard of heavy equipment. To either side of it are comrades-in-arms, fellow vessels who have lived out their retirement and are now paying back their dues, and their souls, to the world. Maritime carcasses lay grisly and exposed to the hot sun while oxyacetylene torches flare in tiny places, slowly eating them away.

Like ants, the first scrappers enter the ship.

The business of scrapping is a specialised task, and the engineers who plan a breaking operation are experienced in their roles and must set out a plan for every ship that arrives in the yard. Many are unique, and all require the creation of a plan that will allow breaking to proceed quickly, efficiently and with some modicum of safety for the labourers involved.

The first operation is delicate: Scrappers, on taking over the vessel, must locate items of particular interest that may be safely sold before the ship is torn apart. Machinery, electronics, furniture, wiring and so-forth that would be difficult to recover once the heavier stages of breaking have commenced. The first scrappers on-board also have a duty of care for the labourers who will start tearing the ship apart, and must locate, mark and remove any hazardous chemicals they find.

But all of this is preamble for what is to follow. The whale, now settled on the beach, its breathing slow and laboured, knows what is coming. The seagulls and crabs, the sand's savage sharp-clawed scavengers, trepidant at first and then with renewed confidence, descend…

…And start to tear it apart.

2: The Diverse Dangers Of Destruction.

Now let’s be real here. Places like Alang and Chittagong are not chosen because they possess a certain sparkle, or because fleet owners are charmed by the place. The great vessels make their final voyages here because the labour is cheap and the price offered is good, and that comes with a certain wilful ignorance of what happens after the ownership is transferred and the cash clears the account.

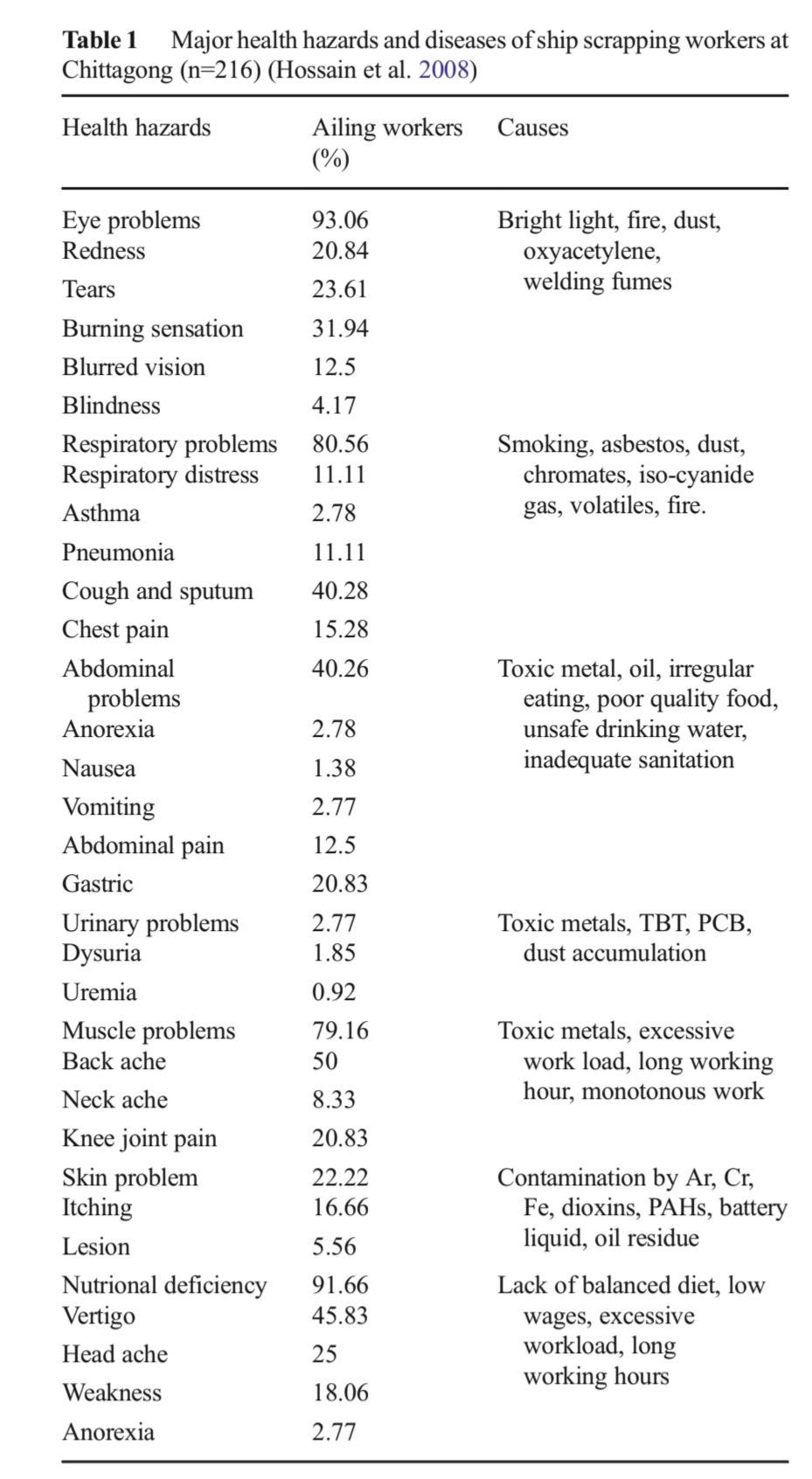

Shipbreaking is a brutal business. One of the world’s most dangerous jobs, its legacy is not just rife with mortality, but all the ailments and health complications that inevitably arise when human hordes are directed to work in close proximity with fuel oils, vapours, powders and chemicals, including asbestos. A 2008 study on the scrappers of Chittagong showed that between 80% and 90% suffered from eye or respiratory problems, another 79% from muscle problems, half with back ache and over 90% with nutritional deficiencies to boot. We are not talking about the mechanised, unionised, cherished industrial employees of the developed world, bound and coddled by employment contracts and standardised work arrangements: The labourers here have historically lived in more desperate straits, which is why industries like shipbreaking come to them.

Things are slowly improving though, as the economies of countries like India leap ahead and workers’ wages rise, dragging the standards of such places up, but nonetheless there remains a certain brutality in the death of steel.

The plans written, the labour assembled, the scrappers are sent to work.

Men with grinders, plasma cutters, torches, winches and heavy equipment start work on the ship’s superstructure, cutting & ripping. Starting at the extremities and moving down the ship as the carcass is stripped, segment by segment. Great chunks fall away, rending titanic concussions and clouds of dust and sand. The air fills with the reverberations of heavy destruction. Coordination becomes a matter of life & death, for the workers cannot be where the titans fall. Slowly, as the body of the great vessel lightens, individual sections are moored and dragged further up the beach for emplaced cranes to process them for further cutting and segmenting.

Eventually, the superstructure of the vessel if sufficiently stripped for the heavy equipment to be revealed; engines and generator systems, valuable in their own right, are assessed and may be lifted wholesale out of the wreck for either re-use or recycling into their constituent parts, whichever is deemed most valuable. Secondary markets spring up around the raw font of steel pouring out of the breaking yards, fuelling the development of real economies beyond the beach-head: A ship is 95% mild steel, plus a couple of percent stainless, and much of this can be re-processed. Bangladesh's annual production of steel rods topped 6 million tons in 2023, and the vast majority of this was sourced from ship-breaking, creating a strange sort of circular economy.

It’s recycling, but not as you know it.

When the raising of buildings, schools, hospitals and apartments in one part of the country can be connected directly to the maritime boneyard in another, it creates a neat symmetry, but this koan of convenience comes at the human cost of chronic ailments and hundreds of deaths.

Beaching, while convenient, is undoubtedly the messiest and most hazardous way to strip a ship. Are there other ways?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Incautious Optimism to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.