I'm a professional cynic but my heart's not in it…

Lies. My heart is definitely in it, and across the span of 42 years of life, 9 years of marriage and 20 years of engineering I've sharpened that pragmatic cynicism to a scalpel that could cut light.

And what I tend to find is that if you hone your cynicism for long enough, it stops being negative doomsaying and loops right back around to become a sort of well-gauged positivity instead, so distilled that it simplifies down to just a few test questions.

There are three of them, they're all one-liners and you can apply them to almost anything.

Want to find out? Let's go…

1: When you hear a shocking number.

“So, is that a lot or a little?”

This is one that might be worth keeping inside your own head, because it won't make you popular at parties… particularly if the line that incites it is “five puppies were drowned in rivers this week.”

But it's a worthwhile question: Maybe five puppies drown every week. Maybe the average weekly puppy count is really fifteen and this is a better than usual time to be a canine.

Either way, you probably don't need to leap straight to installing sniper towers around your dog run.

There's a certain calcined truth to this. Big numbers sound scary, especially when death and injury are involved, but often the big scary number lies couched in an even more gargantuan number that goes completely unsaid. For example, 174 people killed in road accidents is a huge number, poisonously rich in human tragedy. That's 174 families torn apart, hundreds of sirens splitting the air to accident scenes, a million tears shed, hundreds of legacies forever unknown. Tragedy in all forms.

And yet, if this happened across a year in a country of five million people, the big tragic number suddenly isn't so big anymore. It is in fact the 2024 road fatality count of Ireland, which was among the safer countries in the safest continent to drive in. That's no kind of solace for the families of those involved, but it should probably gauge the national response a little.

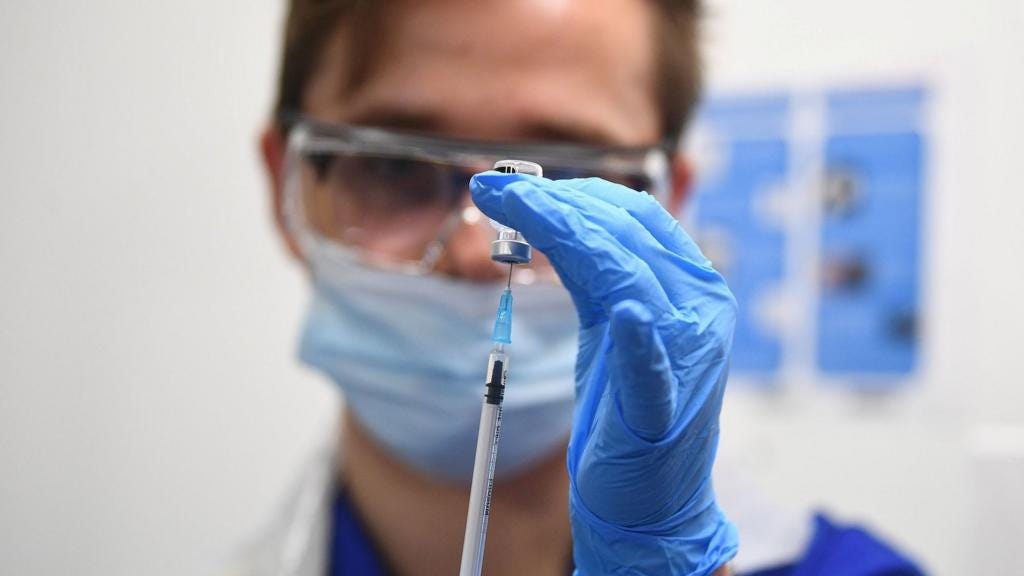

We saw a similar thing during the Covid pandemic with reports of rare blood clotting reactions for people taking the Oxford University-Astrazeneca vaccine. This was particularly alarming given that this was the low-cost one designed for mass production in India and mass dissemination on the subcontinent. Cue media scare stories and millions of people stating they'd sooner cut off their own knuckles than take the Oxford jab.

So ask the question of the clotting rates: Was it a lot or a little?

The rate was about one in 50,000, of which a fifth resulted in fatality: Pretty unpleasant, all said, but about as safe as ten or fifteen commutes on Irish roads, and I do that without thinking. Obviously if it was a choice of this vaccine and one of the others without the blood clotting risk, I'd take the other one, but if the Oxford jab was the only one available it'd still be worth doing. It's many orders of magnitude safer than catching Covid-19 without a vaccination, even if you're pretty young and healthy.

Though not quite as safe as a drive on Irish roads.

Like I said: Is it a lot or a little? It's almost always a worthwhile question to ask… But maybe don't bring it up at a party, you ghoul.

2: When you get told a shocking thing.

“Has this only just started happening, or have you only just started looking for it?”

A couple of engineers came to my desk one day, and something troubling they had to say…

The first stage of contact lens manufacture involves injection moulding: Not of the lenses themselves (that would be crazy) but of the extremely tightly-specified plastic moulds into which a UV-curable monomer solution would be injected. The injection moulding process itself is fast-paced, thumps out huge arrays of lens moulds every few seconds, and has a list of control variables as long as your arm.

It's kinda important.

(Media-friendly image above. Not actually me.)

Anyway, the faces of these two engineers were troubled because in a trial of new lens geometries on a new process, spiderweb-thin strands of flash a few millimetres long were projecting from some of the moulds. It was rare, and couldn't threaten the lenses themselves, but it could cause rejects further down.

They were asking if they could machine a modification to the assembly fixtures (of which there were many hundreds) to make them immune to the effects of the silken strands. Sounds fair enough, though it would cost a six figure sum and could have other unforeseen effects.

So, the question: “Is this new, or is it that we've only started looking for it now?”

I didn't phrase it quite like that. Instead, I asked what the background rate of this failure was on the few dozen production lines on the other side of the wall, that had been thumping out millions of lenses a day for decades. The two engineers couldn't say, which meant that it wasn't as dumb a question as it sounded like.

Anyway, it turned out that this failure was pretty well known by the moulding guys, was never logged and was also fixable at source, which our project’s overworked moulding engineer then went and did, without anyone having to cut metal or spend money.

Sometimes asking a silly question can pay dividends.

And you don't need to be an engineer to ask it…

Last year, a freak occurrence made headlines as flight SQ321 from London to Singapore hit clear air turbulence that threw the giant Boeing 777 so violently that scores of passengers were hurled into the ceiling. Amidst the many minor injuries were seven critically injured and one, a 73 year old British man, dead, possibly due to a heart attack. This horrific incident, savage and without warning, was the first turbulence related fatality in 25 years of civil aviation.

In the days and weeks after this, story after story appeared of aircraft hit with severe turbulence, from all corners of the world. To any casual observer it looked like the opening of a disaster movie: Something subtle and awful had changed in the world, and now the sky itself was turning against us.

… Except, it wasn't.

On average there are about 100,000 flights a day, carrying upwards of ten million people every time the sun comes up. A tiny minority of these will have an episode of bad turbulence, and always have. Aircraft are designed to cope with it, and while not harmless it's usually so competently managed that no newspaper ever pays attention.

So remember our question: “Has this just started happening, or have you only just started looking?”

We'd only just started looking. This was a media storm of a couple of weeks, before the world forgot all about it and moved onto the next big thing. The climate hadn't changed, the neutrinos hadn't mutated and the end times weren't coming. Turbulence was rare and occasional then. It's rare and occasional now.

No need to panic.

So we're down two cynical questions, but now for a third one, and this one's a lot more optimistic than the other two.

3: When someone has a shocking idea.

“What's the worst, and the best, thing that could happen?”

Success and failure are rarely symmetrical, and some things are almost certain to fail. It doesn't mean that we shouldn't do them.

No matter how long in the tooth I get, I'll remember the frisson of excitement in young me if I caught the eye of a nice girl in a bar. Any man knows that feeling: Do I stay or do I go? Ask her out or chicken out? It's one of those little fulcrum points that your entire life could tip on without your knowing: Get it right and a completely new world could stretch out in front of you, full of trials, tribulations, stories and passion.

Get it wrong and… well, you'll feel like a bit of a tit.

Most men know that in that situation, you're almost certain to leave feeling a bit stupid, but maybe just spin the wheel anyway, right? The roulette wheel of life has to hit lucky 36 eventually.

“What's the worst and the best thing that could happen?”

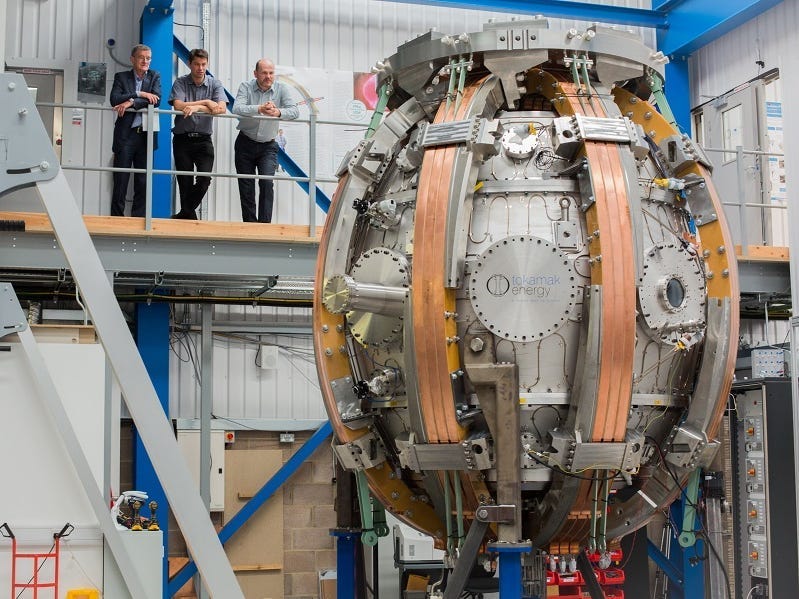

In the South of France, and many less picturesque parts of the world, extremely clever people are flocking to build fusion reactors. Their methods differ, but in all cases the hottest thing in the solar system is corralled by science and superconductors to turn money into magic.

Quite a lot of money. Fusion is difficult.

In other parts of the world, particularly in old NASA warrens aged by 60s successes and the ghosts of dead cigarettes, dreamers dream of humanity colonising the solar system.

It's easy to mock such Hail Mary optimism, but the cynic's lament misses the point… what if it works?

If fusion power, truly intelligent AI or human colonisation of other worlds doesn't work then… so what? You're down a few billion. There'll be another few billion along directly, that's how money works.

But if it works, you might just change everything.

So spin the roulette, launch the Mars rockets, fire up the fusion reactor, buy the girl a goddamn drink! What's the best & worst that can happen?

Unless you're married anyway. The answer to that question works both ways, after all.

Star In A Box

A couple of months ago, in a dull Tungsten & Beryllium doughnut in Cadarache, France, a wispy ring of plasma flashed into fusion fire. For 22 minutes it was the hottest thing in the solar system, before guttering out like God's own candle.